ON BEHALF OF MY GRANDMOTHER:

A RECOLLECTION AS RECOUNTED BY HER GRANDSON

(My grandmother’s story below illustrates the pursuit of the American Dream in a time of deep suffering and shows how a family’s resilience and determination came to be eventually rewarded.)

I was born in Germany in 1941, four years prior to the end of the Holocaust. I was a very young girl and was never to have siblings. Growing up, I did not understand why I did not have a father. According to my mother, my father had tragically drowned in a nearby lake.

I remember hearing mysterious creaks in the ceiling of our house, but my mother reassured me that noise was just due to the scurrying about of mice. Unbeknownst to me, it was actually my father, who was still alive and had been hiding in our attic for years, for he was of half-Jewish descent.

On a day I remember very well, I had just walked home from school, only to find my mother talking in a hushed tone to a strange man. It was shortly after that I learned he was, in fact, my father. My parents were riven by the fear that I would tell somebody that my father was alive and in hiding. My father had nearly been apprehended twice by the Nazis and had thankfully managed to hide behind the front door and behind the furniture on separate occasions.

Fortunately, I was able to grasp the danger and never told a soul about my father. I developed an ever-so-evasive tongue that neither lied nor told the truth. When neighbors asked me, “Where is your daddy?”, I would look at my mother with a face of naive confusion and say, “Why are these people so nosey?”.

Earlier, my mother had a Polish refugee build a bunker in the basement with a trapdoor covered by a rug in our home, creating a perfect place to hide and more importantly for my father to listen to “The Voice of America,” the outlawed radio station that reported on the current events of the war. My father spoke English, which meant that he was able to remain informed on what was happening in Germany at the time, unlike most.

In 1945 when the war had ended, my father dreamed of a life outside of Germany; he wanted to leave the atrocities of the war he had experienced behind, and perhaps to begin a new life in America, the land of the free. Although he would often talk in a hushed voice to my mother, from what I could understand he feared the return of the Nazi regime; if not that, he worried the eternal anti-Jewish sentiment would continue to live on in Germany. According to my father, there were no prejudices in America, and the people remained equal and free.

We would continue to stay in Germany for some time, where I would go on to attend a parochial school, where corporal punishment was common. My caring mother would later transfer me to a non-religious school, as she never liked the punishment the nuns administered. She hadn’t anticipated that at my new school, the boys would call me Jew, and at times even throw jagged rocks at me wrapped in a thin layer of snow as I walked to and from school. Fortunately, my time in Germany soon came to an end, when my father was able to land us a sponsor in America from an organization called the International Rescue Committee.

A man named Jeep, an acquaintance of my father from the American Army, implored my father to take my mother and me immediately to Georgia in the United States as soon as we got our visas. Jeep had painted a lush, rosy image of the American Dream in Georgia, and had certainly intrigued my father. The departure process was arduous, taking us no less than 6 weeks to finish our inspection at a camp in northern Germany. We had been investigated for criminal activity as well as for our health status and family history.

In March of 1952, a few days before my 11th birthday, and approximately 7 years after the end of WW II, my parents and I immigrated to the U.S.

We found ourselves on a boat known as a troop transporter, and high winds whipped the vessel around like a small toy on the high seas. Everyone became seasick; our accommodations were army-style bunk beds and hammocks. The food we were served was cafeteria style and very strange to us; it came out of cans and bore little resemblance to the home-cooked food that I enjoyed back in Germany.

It was evening when we began docking in New York, and our first impression of the U.S. was the Statue of Liberty, illuminated by large gleaming lights. The night air was salty and crisp, and the streets were flooded with cars being driven at thrilling speeds alongside the water. My mother wept, for it had been her dream for many years to eventually see the statue. After two weeks of settling down in New York, we departed by train for Georgia, eager to experience the lush life that Jeep had painted.

The train ride was fairly calm, as people spoke in complex and mannered tones of English that I could not yet understand. The English language intrigued me, and I wished to soon begin learning how to speak it. As I looked out the window, the moment seemed surreal, for I could not believe that, after so long, I was finally in the country of freedom.

When our train briefly stopped in Virginia, I began to realize the fallacy behind the perfect rosy life in America I had imagined. As I departed the train, ahead of me in the distance lay clusters of disheveled shanty houses, occupied by crowds of dark-skinned people. The shacks were flooded beyond capacity with inhabitants, and the rotting stench in the air was palpable. The shacks seemed to be constructed from plywood, plastic, and miscellaneous discarded pieces of garbage which must have been contributing to the pungent odor.

I quietly stood in place, forgetting all together that I was blocking the train’s exit. Snapping out of my shock, I hurriedly stepped aside and turned back to face my parents, who seemed equally dumbfounded, for we had never seen such poverty back in Germany – even in its worst times.

Once in Georgia, our days were disappointingly mundane and quite uneventful. Later during our stay we boarded a bus in order to visit a nearby part of Atlanta. We were seated near the front of the bus. It was not long before the bus stopped, and a dark-skinned older woman boarded the bus. I immediately sprang to my feet, offering my seat as was the common custom in Germany. She scowled at me, unappreciative of my offer, and brushed past me towards the rear of the bus. My parents and I were surprised, for we did not understand why her demeanor was so cold toward me. It would take time before we learned about the extensive racial segregation in the United States. After fleeing mass discrimination and genocide in Germany, my parents and I were certain that we did not want to live in the South. I wanted to believe there was more to America than what I had seen in the South, and would later find that to be true.

Many decades later, my father would ironically end up retiring back in Augsburg where he eventually received only a small compensation for lost property taken by the Nazis. Fortunately, my father lived to see the Berlin Wall come down, which gave him hope for the future. I was now married with three sons and a daughter, who also were able to experience the fall of the Berlin Wall. My mother would sadly lose herself to dementia.

I am still ever grateful that my children have been able to live the American Dream in California, and that my family’s blood will continue to see the dawn of the future.

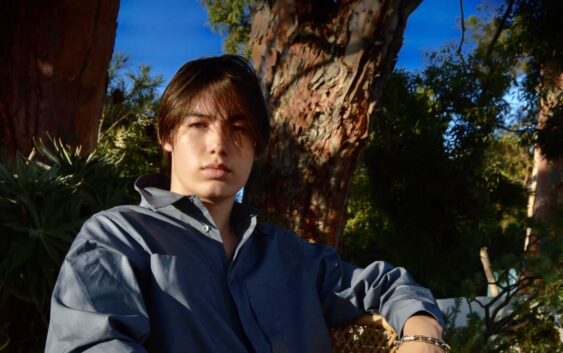

Three generations of the Seton family: Grandmother Karin, Grandson Milo, Grandfather Gil, Sr., and Son Gil, Jr.